History

© Pixabay, CC0

When Werner von Siemens became a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences in 1873, he was honoured only as a scientist, not as an inventor or industrialist. This was emphasised by the academy and it is also how Siemens himself recalled it in his memoirs. Engineering was considered to be an applied natural science and not a discipline in its own right well into the 20th century.

Perhaps because this assessment is quite at odds with the social and economic importance of the engineering sciences, the Academy made great strides forward in the 1990s.

The early days

The first initiatives to establish a National Academy of Science and Engineering date back as far as the German Empire. The signs were positive at the turn of the century, yet it would take almost another 100 years before the Convent for the Technical Sciences was established.

Looking back to the German empire

From a historical perspective, the trip back to the German Empire starts in the year 1873, when Werner von Siemens became a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin. This honour was explicitly in recognition of Siemens as a man of science, and not as an inventor and industrialist.

This was emphasised by the academy and Siemens himself highlighted it in his memoirs. In the early 1890s, the mathematician Felix Klein presented a first draft for an Academy of Engineering Sciences.

Klein’s idea was that the Göttingen academy be expanded to include engineering subjects, but his plan was unsuccessful.

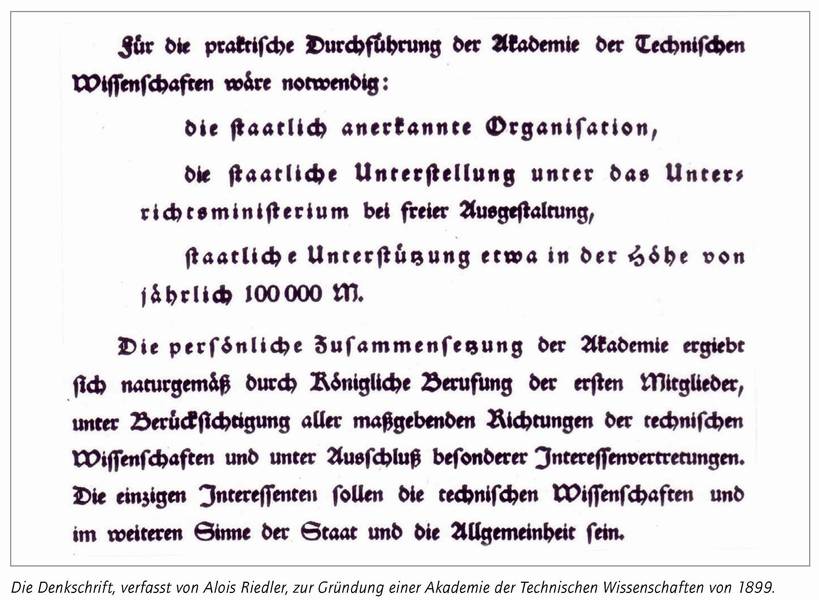

Alois Riedler’s memorandum

Another attempt was made by Alois Riedler, a professor of mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin, who took advantage of his proximity to technology enthusiast Kaiser Wilhelm II and presented the Emperor with a memorandum on the foundation of an Academy of Engineering Sciences in 1899.

Riedler believed that the academy – established initially as a Prussian foundation but with the possibility of becoming an empire-wide institution – should act as a bastion for the engineering sciences and provide social recognition for work in this field. He proposed that the Academy of Engineering Sciences be set up as a state-approved organisation that would be affiliated with the Ministry of Education and have the freedom to define the subject areas to be covered.

He envisaged an annual financial requirement of 100,000 marks in the form of state support, with the remaining funds to be raised through donations and contributions from interested companies. The academy’s areas of responsibility would include the promotion of science, technology development and policy advice.

Do engineers have a place in an academy?

Critics rejected “as unwarranted and questionable” the proposal that the academy advises on policy. On the other hand, Riedler’s ideas regarding the “promotion of economic research in engineering and the establishment of a supreme technical body to answer practical questions” were supported.

However, the main focus of all the criticism centred around the position of the engineering sciences, which were not recognised as having an equal status within the sciences. In contrast to the seminar-based humanities and natural sciences, they were viewed purely as application-oriented. The term “applied” sciences was used well into the 20th century to make a clear distinction between engineering sciences and basic research.

The reservations surrounding engineering sciences were still very much in evidence in 1900, when the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences celebrated its bicentennial. To mark the occasion, the Emperor awarded the academy five seats for full members; engineers were to be given preference for three of those seats. This once again gave rise to the debate on the scientific value of engineering disciplines.

While these had gained a certain amount of equal status academically with the entitlement of engineers to pursue a doctoral degree, in the eyes of the scientists who were already members this did not justify their admission to the academy. The structural engineer Heinrich Müller-Breslau and the electrical engineer Friedrich von Hefner-Alteneck were appointed; the third position remained vacant. The academy was intended to remain a place of “pure” science. It was only in the mid-1920s that the physical and mathematical class in the Prussian Academy of Sciences could decide to admit Karl Willy Wagner and Johannes Stumpf, two leading exponents of the engineering sciences, as full members.

Previously, the academy had turned down the application made by the Reichsbund deutscher Technik to incorporate an engineering class in the academy.

Rapprochement between the academies and the engineering sciences

A rapprochement between the academies and the engineering sciences only took place after World War II, initially in the eastern part of Berlin at the Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften, which revived the Leibnizian dictum of Theoria cum praxi with the introduction of a class for engineering sciences in 1949. However, this only lasted for a brief period and this class had already disappeared again by 1954. The engineering sciences, mathematics and physics now formed one class. It was only in February 1989 that the Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR once again introduced a class for the engineering sciences. When it came to the establishment of the North-Rhine-Westphalian Academy of Sciences, Humanities and Arts (NWAW) in 1970, a class for the natural sciences, engineering sciences and economics was put in place from the start.

At the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities (BBAW), founded in 1992, the five classes available included a class for the engineering sciences from the very beginning. This is where the more recent history of acatech begins.

From convent to academy

There was a long gestation period, but then events speeded up. Within ten years, between 1997 and 2007, acatech was upgraded from a convent to a national academy.

National academy within ten years

On 21 November 1997, the constituent meeting of the “Convent for the Technical Sciences” working group took place in Berlin. Following years of efforts, this initiative of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities and the North-Rhine-Westphalian Academy of Sciences, Humanities and Arts led to the establishment of the first group to represent the interests of the German engineering sciences at science academy level. Günter Spur was elected chair of the convent at the inaugural meeting. The initial 50 or so members came predominantly from the engineering sciences, or rather from the natural science, engineering and economics class of both founding academies.

From the very beginning, the Convent for the Technical Sciences set itself a number of tasks: promoting research and the next generation of engineers; intensifying international cooperation; and engaging in dialogue with the natural sciences and humanities, policymakers, business and society as a whole on the role of future-oriented technologies.

Establishing the convent

With a view to putting the further development of the Convent for the Technical Sciences on a broader footing, the presidents of the seven German science academies decided in April 2001 to consolidate all national science and engineering activities at academy level under the umbrella of the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities. Thus, the Convent for the Technical Sciences of the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities was established on 15 February 2002 and an application was subsequently made for its entry into the central registry of associations (Vereinsregister) and to award it non-profit status. Joachim Milberg took on the role of Chairperson of the Board, Franz Pischinger became his Deputy (in May 2003, these offices were renamed President and Vice-President, respectively, following a change to the articles of association). The convent decided on a pithy short name for itself – akatech – the spelling of which was later changed to “acatech” to make it more suitable for international use. The name represents the symbiosis of academy and technology to which acatech aspires.

acatech as a working academy

Since it was established, acatech has grown consistently through elections and currently counts around 400 members from academies, universities, research institutes and commercial enterprises from across Germany and abroad. As acatech was designed as a working academy from the start, the substantive work is concentrated in working groups. In 2002 and 2003, a total of seven working groups were set up; these address future-related research and technology policy issues.

At an international level, acatech performs its functions today through its membership of the European Council of Applied Sciences, Technologies and Engineering (Euro-CASE), the European non-profit organisation of national academies of engineering, applied sciences and technology. acatech also belongs to the International Council of Academies of Engineering and Technological Sciences (CAETS).

acatech is advised by a Senate on substantive and strategic issues. The Senate is made up of prominent figures from science organisations and commercial companies. The former President of Germany, Roman Herzog, was Chair of the Senate from 2002 to 2012. In June 2012, he handed over the baton to Ekkehard D. Schulz. In September 2003, a friends association, the Kollegium, was established. The purpose of the Kollegium is primarily to help provide financial support for acatech.

At the beginning of 2008, acatech was upgraded to a national academy in receipt of funding from the Federal Government and the Länder. The Convent for the Technical Sciences of the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities became acatech – National Academy of Science and Engineering.

Günter Spur – looking ahead, shaping change

Günter Spur had played a significant role in the establishment of the National Academy of Science and Engineering. This acatech pioneer died on 20 August 2013. In this special publication, close associates remember the scientist and the man.

Günter Spur: Looking Ahead, Shaping Change (in German)

Roman Herzog – pioneer, motivator and supporter

Former President of Germany Roman Herzog was a pioneer, motivator, supporter and long-standing Chair of the Senate in the Academy. He died on 10 January 2017. In honour of the occasion, Joachim Milberg, Founding President of acatech, paid tribute to Roman Herzog’s commitment to innovation in Germany and to acatech.

Innovation begins in the mind: in our attitude toward new technologies, toward new types of work and training, quite simply in our attitude toward change.

Former President of Germany, Roman Herzog

In memory of Roman Herzog: “Innovation starts in the mind”

Commemorative address by Joachim Milberg

Marking the state occasion and funeral service for former President of Germany Prof. Dr. Roman Herzog, President Joachim Gauck paid tribute to his commitment to the willingness of Germany and its citizens to change. “He was good for us Germans.” Roman Herzog was also more than good for acatech! His commitment to our Academy stemmed from his conviction that only constant renewal safeguards the future. In sadness and in gratitude, I remember Roman Herzog, who played a crucial role in supporting the establishment of acatech and decisively helped to shape the development of the Academy as Chair of our Senate.

In his proverbial “jolt speech”, Roman Herzog said:

“This is not just a matter of technical innovation and of turning research into new products faster. We are witnessing nothing less than a new industrial revolution, the development of a new, global society in the information age.”

Even in this pioneering “Berlin speech” in 1997, he emphasised the ability to renew as the most important prerequisite for economic, ecological and social stability and sustainability.

“Innovation begins in the mind: in our attitude toward new technologies, toward new types of work and training, quite simply in our attitude toward change. I would go so far as to say that Germany’s attitude and mentality has a greater impact on its status as a centre of business and industry than its ranking as a financial centre or the level of its non-wage labour costs. What will decide our fate is our ability to innovate.”

As early as the mid-1990s, he was pursuing, together with the then Minister for Research Jürgen Rüttgers, the idea of establishing a national academy of science; to his great regret, this was initially unsuccessful. Shortly after his term as President of Germany came to an end, I put to him the idea of a “National Academy of Science and Engineering”; he was immediately fascinated by the proposal. During his period in office, he had felt very keenly that Germany lacked a strong voice in the area of science and engineering. Looking back at his presidency, he wrote in 2007:

“During my term in office, there was no truly important forum, before which I could have presented my ideas about the need to make technological progress and the need to create a discipline focused on technological progress and which would have attracted sufficient publicity.”

Roman Herzog’s support in establishing acatech was invaluable. His contribution to our cause goes far beyond the symbolic. acatech’s Senate was constituted on 30 September 2003 and Roman Herzog assumed the role of Chair.

The first acatech gala took place on the same day in the Konzerthaus (concert hall) at Gendarmenmarkt in Berlin. Berlin’s “front room” was full when acatech introduced itself for the first time to a wider public. We owe this great public visibility in no small measure to the keynote speakers, who expressly advocated for the establishment of a National Academy of Science and Engineering: former President of Germany, Roman Herzog, and German Chancellor, Gerhard Schröder.

When Roman Herzog took on the role of Chair, our Senate consisted of 37 figures from the worlds of business and science. The Senate acted and continues to act as the link between science, business and politics, and acatech works at the interface of these three domains. Under the chairmanship of Roman Herzog, the Senate more than doubled in size.

The particular dedication shown by leading minds in the innovation-oriented scientific institutions and technology-oriented companies is testament to the fact that the establishment of a National Academy of Science and Engineering had been long overdue. The time finally came in 2008. The federal states and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) headed up by Annette Schavan agreed to the joint funding of acatech. Then German Chancellor Angela Merkel said at our gala in 2008:

“Since 1 January this year, for the first time in German history, there is a national academy that provides policymakers and the public with comprehensive and competent advice on science and engineering questions by first of all forming an opinion and then disseminating it. This is an institution that has become the voice of science and engineering, an important voice in our country for promoting growth and innovation.”

Roman Herzog was a great statesman and above all a great character. He was an important, and indeed perhaps our most important, partner and a driving force from the world of politics and civil society. As a person, he was both thoughtful and dynamic; as a speaker he could sound a note of caution yet still retain a sense of humour. At our first symposium, he asked what the difference was between a tin can and a locomotive. He said that if the question is whether a person can shave with one or other of them, then there is no difference. He compared this with the debate on whether better growth would be promoted by lower taxes or higher expenditure.

“We have to see that there will constantly be innovation, that there will constantly be new products, that there will constantly be new services that we can offer … That is the real reason why we have come together here today and why we must continue to persevere.”

Roman Herzog had this conviction as President of Germany and as a pioneer and a trailblazer for acatech’s cause. He greatly emboldened Germany and he greatly emboldened us here at acatech. The National Academy of Science and Engineering will continue to raise its voice in a way that he would approve of and bolster the confidence of people in their ability to innovate and thus enhance the future viability of our country.

We will cherish his memory!

Prof. Dr.-Ing. Joachim Milberg

Founding President of acatech

Science academies in Germany

acatech was established against the backdrop of a long tradition of science academies in Germany. Before acatech, it was primarily scientists from the natural sciences and humanities scholars who joined forces in these academies.

More

acatech was established against the backdrop of a long tradition of science academies in Germany. Before acatech, it was primarily scientists from the natural sciences and humanities scholars who joined forces in these academies. The oldest, and today the only national institution, is the German National Academy of Sciences (Leopoldina), which is based in Halle and dates back to 1652. Eight other science academies also exist at Länder level. The oldest of these, the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy, was established in 1700 as the Kurfürstlich-Brandenburgische Societät der Wissenschaften by G.W. Leibniz. The other state institutes are the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz, North-Rhine-Westphalian Academy of Sciences, Humanities and Arts and Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Hamburg.

There has been organised cooperation between the German-speaking science academies for more than 100 years. This began in 1893 with the establishment of the Verband der wissenschaftlichen Körperschaften, known as the “Cartel”, by the academies in Göttingen, Leipzig, Munich and Vienna. After World War II, the West German academies initially formed a working group as the successor to the Cartel. In 1967, this was renamed the Konferenz der deutschen Akademien der Wissenschaften in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. The Saxon and the Berlin-Brandenburg academies joined in 1991 and 1993, respectively; in 1998, the organisation was renamed again as the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities.

Over the course of the 20th century, national academies of science and engineering sprung up side by side with the existing science academies in nearly all industrialised countries. The oldest of these is the renowned Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA), which was founded in 1919. The British Royal Academy of Engineering, which dates back to 1976, and the Dutch Society of Technological Sciences and Engineering (FTW), founded in 1986, are among the most recently established institutions.

An attempt to launch an academy of science and engineering was made as early as 1899 in Prussia. This was made against the backdrop of the “struggle for emancipation” waged by the science of engineering and the Technische Hochschulen throughout the whole of the 19th century against the established sciences represented at the traditional universities. In 1899, the Technische Hochschulen scored a significant victory when they obtained the right to award doctorates. The initiative for the new academy came from the Berlin-based mechanical engineering professor, Alois Riedler. It was intended to promote the further development of engineering, the advising of policymakers and the greater sharing of the engineering sciences with business and society as a whole. The Emperor and Prussian King Wilhelm II supported the proposal, but it fell through at government level. To compensate for this, three positions were created for science and engineering for the first time at the Prussian Academy in 1900. Werner Siemens, an engineer, had been elected to the academy back in 1873, but was explicitly admitted as a natural scientist rather than an engineer.

Other attempts by engineers to create additional positions or set up a separate engineering class came unstuck until after World War II, both in Prussia and at the other German academies. Only the Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR, which emerged from the Prussian Academy after the war, introduced a separate engineering class. In the Federal Republic of Germany, the newly established North-Rhine-Westphalian Academy of Sciences, Humanities and Arts followed suit with a natural science, engineering and economics class. In 1987, the Land of Berlin also established the Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin – from the very beginning, engineering was an integral element of this institution. However, this new academy was disbanded again just three years later in 1990 following the fall of the Berlin Wall. In 1992, the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities (previously the Prussian Academy of Sciences) was reconstituted. From day one, its structure provided for an engineering class.

acatech is continuing the work and has consolidated engineering activities at academy level for the first time in a national context. With the establishment of its own national interest group for engineering, Germany is catching up with other industrialised nations and closing a gap that has become ever greater with the growing importance of engineering in tackling global economic and environmental problems over the course of time.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

1.)Wolfgang König: “Die Akademie und die Technikwissenschaften. Ein unwillkommenes königliches Geschenk”, in: Jürgen Kocka (ed.): Die Königlich Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin im Kaiserreich, Berlin: Akademie Verlag 1999: pp. 381–398.